All right now, OCC, Let me tell you ‘bout Sis Joe this time!

A train song makes you think of traveling, of a good journey, so let’s set the stage.

All right now, boys, Let me tell you ‘bout Sis Joe this time

Sis Joe, on the M & O, Track heavy but she will go

We’re heading out on the Mud Line, which runs between Paducah, Kentucky and Cairo, Illinois on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad Company. It’s the late 19th or early 20th century (1888-1930). The foreman is telling his crew (10-30 men), that we’re taking Sis Joe, which is likely a handcar or a small work train, and we’re going out on the tracks, which need a lot of repair. Track heavy, so they need at least 20 man hours of work. But it’s okay, even though the track needs all this work, Sis Joe can still go.

We’re heading out on the Mud Line, which runs between Paducah, Kentucky and Cairo, Illinois on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad Company. It’s the late 19th or early 20th century (1888-1930). The foreman is telling his crew (10-30 men), that we’re taking Sis Joe, which is likely a handcar or a small work train, and we’re going out on the tracks, which need a lot of repair. Track heavy, so they need at least 20 man hours of work. But it’s okay, even though the track needs all this work, Sis Joe can still go.

Takes a mule, take a jack, Take a lin-in’ bar for to line (this track)

On the Mud Line, on the sand. On the Mud Line, get a man

Jack the Rabbit, on the M&O. Track heavy, but she will go.

The foreman tells his men to get their tools. Take a mule, a jack, grab a lining bar (a long metal tool that is cylindrical on one end and usually has a diamond-shaped point on the other). The rails are out of alignment, something that happens often, and they will use the lining bar (also known as a gandy) to lift and reposition the tracks, so they line up straight. Jack the Rabbit. This is the derail, the siding where runaway trains, cars, engines are shunted to get them away from the main track before they derail. It’s open on the far end to the fields or prairie so the train can just keep going until it stops well away from the main track. The track need work but Sis Joe will go.

Lining the tracks was an important and consistent job. The vibrations and force of the train going through at 30, 40, 60 miles an hour would knock the rails loose and crews had to come and line them up again so trains would not derail. Now this work is done by machine, but back then it took crew of hardworking men.

Let’s step back in our journey, to 1848. River boat travel down the Mississippi River to New Orleans was slow and unreliable, and then even slower as people and goods had to travel over land to get to Mobile, Alabama. A plan was hatched to run a rail line from Mobile to Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers converged. The Mobile and Ohio Railroad Company was born, chartered in Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Work began in 1852, and on April 24, 1861, the track had reached Corinth, Mississippi, just days after the start of the Civil War. The railroad was an important asset for the Confederacy, and it was attacked by both sides, ending the war in total ruin. It was rebuilt and eventually reached Cairo in 1883, using the Illinois Central railroad bridge over the Ohio River. In 1888 work was started on the Mud Line, a spur running from Paducah, Kentucky to Cairo, with the line opening sometime before 1902.

At this point the trip jumps ahead to 1933. John Lomax, a retired banker in his mid-60s convinced the Library of Congress to send him to the South to find and record the working songs of African Americans laborers working on railroads, mines, with cattle, and other such jobs. Lomax thought that the work songs were disappearing, giving way to more modern times and he wanted to record them before they were lost. Lomax believed that he would have the most success by seeking out men who had be incarcerated for a long time, and so he traveled from prison to prison.

“Alan and I were looking particularly for the song of the Negro laborer, the words of which sometimes reflect the tragedies of imprisonment, cold, hunger, heat, the injustice of the white man.” (John A. and Alan Lomax, Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly (New York: Macmillan, 1936), p. ix.)

In Angola Prison in Louisiana, he found Huddie Ledbetter (Leadbelly) and recorded hundreds of his songs and eventually helped facilitate his release from prison.) Lomax next moved on Parchman Farm prison in Mississippi, where he recorded folk songs from a variety of inmates, including an African American singer named Bowlegs, who introduced him to “Sis Joe”. Nothing more is known about Bowlegs. Lomax, like many of the people recording songs at the time, was more focused on making recordings than documenting the people and stories behind the songs. He frequently neglected to include even the names of the singers on the recordings. This seems to be the first recording of Sis Joe. It can be found in the archives at the Library of Congress. Unfortunately, it has not been digitized.

The second time Lomax records Sis Joe, it’s three years later, May 1936, and he’s in East Texas, paying a return visit to Henry Truvillion. Truvillion is an African American preacher and rail crew foreman for a lumber company, who previously worked railroads in Mississippi. Lomax and Truvillion met in 1933, but at that time, Truvillion, because of his faith, was only willing to share spirituals. Lomax returned in 1936 and this time he convinced Truvillion to share other songs, and a variety of railroad hollers, including Sis Joe. (We learned details of these sessions from Truvillion’s son who some years later wrote about the experience.)

Lomax went on to publish Sis Joe and much of the other music he collected in several books. We find Sis Joe in “Our Singing Country (1941)” http://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/our-singing-country/our-singing-country%20-%200362.htm where Henry Truvillion is listed as the author. In this volume we find the music for Sis Joe and the words for “Track Lining Holler.”

It is this version of Sis Joe that we sing now.

Recordings of Sis Joe and other railroad hollers from Truvillion were recorded and are available in the Library of Congress archives. Some of these hollers are available online.

Henry Truvillion, May 1936, East Texas

Unloading Steel Rails

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000264/

Track Lining Holler

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000262/

Track-callin’

https://www.loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000263/

Research suggests that while all railroad workers sang railroad songs, African American track workers were the only ones who had a long tradition of using task-related chants to coordinate their work. This tradition of work chants likely came with them from Africa when they were brought to America as slaves, and they continued the practice here.

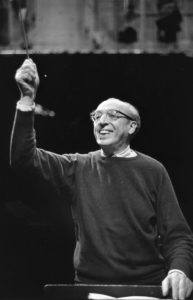

Our journey continues in 1942. Aaron Copland is composing a ballet – Rodeo – with themes from American folk tunes running throughout. The timing suggests that Copland ran across the tune in Lomax’s book when he was researching music for his ballet. In Act One, Buckaroo Holiday, Sis Joe heralds the entrance of the cowboys, with drums mimicking the pounding of spikes as cowboys dance. Sis Joe reappears for a brief moment in Act Four, Hoedown.

Our journey continues in 1942. Aaron Copland is composing a ballet – Rodeo – with themes from American folk tunes running throughout. The timing suggests that Copland ran across the tune in Lomax’s book when he was researching music for his ballet. In Act One, Buckaroo Holiday, Sis Joe heralds the entrance of the cowboys, with drums mimicking the pounding of spikes as cowboys dance. Sis Joe reappears for a brief moment in Act Four, Hoedown.

Naturally, as a Copland fan and someone who has listened to Rodeo many times, I had to play it again. And that naturally led to listening to more of Copland. And there, in Emblems (1964), for one brief moment, is Amazing Grace. That is when it dawned on me just how much our Spring program intersects with Copland. We have the three pieces from his Old American Songs: Simple Gifts (which also wafts through Appalachian Spring), At the River, and Ching A Ring Chaw as well as Sis Joe and Amazing Grace.

Our journey continues in 1996. Composer Jackson Berkey (born the year Rodeo was composed) was commissioned to write a piece by Dr. Charles Smith for the Hastings College Concert Choir tour to Japan in March of that year. The result was “Sacramento – Sis Joe.”

Bringing us to Thursday nights in Truro.

By Karen Strauss